Seattleite Sekiko Sakai tells the story of how her family benefitted when her father, Nobuhiko Sakai, a Northwest Kidney Centers patient, received palliative care through a unique partnership between Northwest Kidney Centers and Providence Hospice of Seattle.

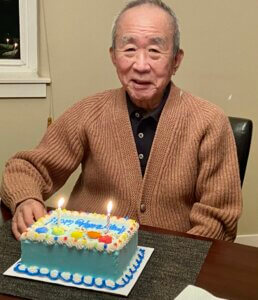

Nobuhiko passed away in 2021. Nobuhiko’s last year and a half included many highs and lows, but ultimately Sekiko calls the period “a blessing.”

I’m coming home with my dad

For years he’d say his kidneys were fine. In his mind I think starting dialysis meant the end of his life. Then he called and asked me for my help after his operation to get a Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) port and with training. So, I flew to Los Angeles to help.

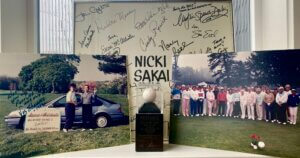

My father was sent to New York in the early 1970s by the Japanese company he worked for and after four years, he cut ties with the company deciding to stay in the United States and start his own import/export company. He loved it here and wanted to raise his kids here. Starting over was not easy but through his ability to network, he built a successful business and served as its CEO. To bring together the two cultures he loved, he was an early and longtime consultant for U.S. companies doing business with Japan. He also used his love of golf to tie the two cultures together, organizing Pro-Am (professional-amateur) tournaments that brought business executives from Japan to play golf with women from the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) to raise money for charitable causes.

After the surgery to get a PD port, doctors could not sign off on him being solely responsible for his dialysis treatments due to some memory issues made worse by the anesthesia.

We agreed he would move to Seattle and start PD there. He would face a new environment unexpectedly at age 84 (one month before of his 85th birthday). We packed his things in mid-February 2020, just before everything shutdown due to COVID. I remember calling my husband and saying, “I’m coming home with my dad.”

My husband is an anesthesiologist and my daughter and son worked in the medical field so I figured we wouldn’t need as much medical help as most families. I didn’t know how important psychological support would be for us.

My dad started PD with Northwest Kidney Centers and felt better than he had in a long time. But soon he switched from dialyzing at home to getting his treatments three days a week at the dialysis clinic.

All the while, he was going back and forth about whether to keep dialyzing or not.

He liked going to the clinic and took care of getting there himself. He felt very respected. He liked seeing the staff and the other patients. Even though he was often quiet, reading or on his tablet, he was always aware of what was going on. He had good days and bad days.

Some days he’d say he could do this another two or three years. On the worst days he would say, “It was a bloody day. I don’t want to do this anymore. I want to call the doctor and stop next week.”

The hardest part for us was his flipping back and forth. He would change his mind every day sometimes. We were emotionally exhausted. We would try to wrap our minds around the idea, and then he’d say, “I’m feeling great. I’m going to continue.”

Palliative care – support for the whole family

About this time we connected with the kidney palliative care team at Northwest Kidney Centers, led by Dr. Dan Lam.

Palliative care is specialized care for people with serious illnesses that focuses on minimizing pain, symptoms and stress. The goal is to improve quality of life, and that is done by treating the whole person and not just the illness. Palliative care addresses the emotional, spiritual and psychological sides of disease.

“What matters most to patients is how to live well with the optimum quality of life,” says Dr. Lam, “and that varies from patient to patient.”

“You have to give the person all the time they need and allow them to change their minds multiple times, even every day, depending on how they feel,” he says. “Patients need space and patience in the last days of life for closure and more.”

Once in May 2021, my father decided to quit dialysis. I called his younger brother in Mexico to say Dad is giving up his dialysis, which means he has a couple of weeks to live–if you want to see him again, then now would be the time. Luckily an emergency visa was granted through Sen. Maria Cantwell’s office.

Nobody could go out due to COVID. Even my kids were at home. It was a silver lining to be trapped together every single day. My uncle was a professional sushi chef, and we had sushi on so many nights, Mexican dinners too. We shared really amazing meals at home and did some fabulous things. Dad really enjoyed the family time.

During the time Dad decided that he wanted to continue with dialysis.

Dr. Lam was so helpful then, reminding us that people in palliative care need the time they need to get closure, whatever it might be.

One night on a family Zoom call, Nobuhiko’s nephew who lives in London asked, “Can you tell me about your grandfather.”

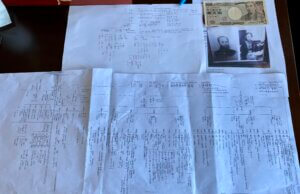

He also asked about other ancestors I knew nothing about. My father said he didn’t know and then walked out of the room. He came right back with a large sheet of paper, an extensive family tree, handwritten by his mother that went back five generations to the 1600s. Dozens of the names included the character for doctor. My kids took immediate interest.

My great-great-great grandfather is considered the father of modern medicine in Japan, with documentaries and books about him. My great-grandfather was a founding benefactor of Keio University. My father took a photo of an ancient scroll in a city hall of an original letter that the founder wrote asking my great-grandfather to fund the school.

There’s this incredibly rich family history that I didn’t even know existed. None of the kids in my generation knew it at all. Had he not been living here with us, none of this information would have come up. I would have found these amazing items going through his things after he passed.

My father was delighted my cousin took interest. He didn’t think anybody was interested and really wanted to tell the stories. It was one reason he hadn’t quit dialysis.

We all knew that after he had retired, he moved to Japan to teach English (ESL) and was living in a rural area where he felt the students needed help the most. What nobody knew was that on weekends, he’d travel all over the country doing research on the family history. My father even went to Tokyo University to look for my grandfather’s graduation certificate but actually found research papers he wrote when he was getting his medical degree.

Dad had kept all the details of his time in Japan to himself. But he wanted to tell his story, and its part of the family’s lineage. He wanted to tell the experience of a young Japanese immigrant who came to the United States with his family in the 1970s, about the success he achieved through hard work and struggles, about being a groundbreaking businessman and cultural ambassador for both countries.

Thankfully he was able to do that. He would tell me about the relatives, and I would show him charts and family pictures. I did the best I could to record all the stories that he could remember and told him I wished we’d started 10 years ago, when his memory was better and he felt better.

His friend in Hawaii told me that Dad said he felt like he got all the stories out.

He wasn’t really ready to go until he felt like he could share his legacy. There would have been no closure. It was something that he needed to do. All of it was a blessing.

He wouldn’t have gotten the time with his family and grandkids, the time to reconnect with my cousins. He wouldn’t have been able to give us the gift of his and our heritage.

* * *

Following several rough days that included two incidents where he was found on the floor, having fainted or fallen, and which resulted in emergency room visits, he made the final decision the stop dialysis treatments.

Nobuhiko Sakai passed away July 18, 2021, at the age of 86. Sekiko’s kids traveled to Japan and scattered Nobuhiko’s ashes on the summit of Mt. Fuji at his request 50 years after he had gone to the United States.