By 1960, it was apparent that an artificial kidney could successfully treat someone with kidney failure. The challenge, however, was in repeated treatments; each treatment so damaged the veins and arteries at the access point that ongoing treatment was not possible.

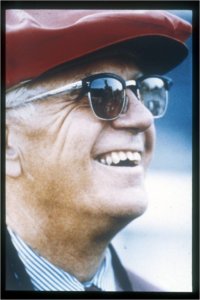

That year Dr. Belding Scribner of the University of Washington treated a man from Spokane who had responded very well to acute dialysis, going from being in a uremic coma to being up and around and feeling fine. Scribner knew too well the patient could only survive with ongoing dialysis, an option that was not available.

According to Scribner, “We did the only thing we could do. We had an agonizing conversation with his wife and told her to take her husband back to Spokane where he would die, hopefully without much suffering. He died quietly (at home) about two weeks later. The emotional impact of this case was enormous on all of us, and I could not stop thinking about it.

The magic moment

“Then, one morning I woke up about 4 a.m. and groped for a piece of paper and a pencil to jot down the basic idea of the shunted cannulas, which would make it possible to treat people like the Spokane patient again and again with the artificial kidney without destroying two blood vessels each time.

“Then, one morning I woke up about 4 a.m. and groped for a piece of paper and a pencil to jot down the basic idea of the shunted cannulas, which would make it possible to treat people like the Spokane patient again and again with the artificial kidney without destroying two blood vessels each time.

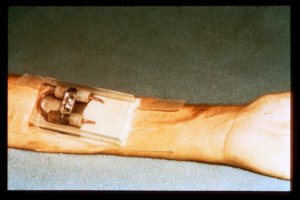

“And, indeed basically it was such a simple idea – just connect the tube (cannula) in the artery to the cannula in the vein by means of a connecting tube or shunt, and the blood would rush through without clotting and maintain the cannulas in a functional condition indefinitely. Then when an artificial kidney was needed, we could simply replace the shunt temporarily with the blood circuit of the artificial kidney.

Soon thereafter in a casual conversation in a stairwell at University Hospital (now University of Washington Medical Center), Scribner heard about a new material called Teflon, which would not result in blood clotting.

“The most amazing thing about the idea was that unlike most such ideas it worked right from the start.”1

The magic moment takes flight

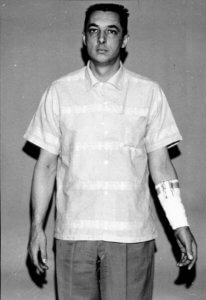

Days later Scribner met with Wayne Quinton, manager of the hospital’s medical instrument shop, and Dr. David Dillard. Quinton created the first shunts using Teflon and continued to improve their design over time. Dillard’s patience and surgical skills allowed the shunts to be attached safely and effectively to ensure their ongoing success.

In 1960 there was no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or device regulations, and so fortunately, there was no need to conduct animal experiments with the shunt before using it in patients.

Today millions of people around the world are alive thanks to the availability of dialysis treatments, which most patients receive three times each week. Shunts are largely obsolete, having replaced by what are called fistulas and other access methods.

1 From Miracle to Mainstream: Creating the World’s First Dialysis Organization by Dr. Christopher Blagg, a colleague of Scribner’s and Executive Director of Northwest Kidney Centers for nearly three decades.